by Kathleen Brophy

New breaking story just in; Western nations are economically exploiting African countries. If this sounds familiar, that might be because it is. For any student of African history, this type of headline would hardly stir a reaction. But, tax justice advocates in many African countries are hoping to highlight the issue afresh by taking on a particularly menacing form of economic exploitation in a new “Stop the Bleeding” campaign launched this past Summer.

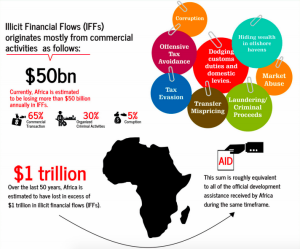

The new campaign seeks to bring attention to the issue of illicit financial flows or “IFFs”, a form of illegal capital flight that has become a commonality arising out of the shadowy architecture of today’s international finance system. This architecture consists of innumerable vehicles that exist solely to help international global elite avoid and evade taxes as well as hide, transfer and launder money. This kind of activity takes place in a growing number of “secrecy jurisdictions,” also known as tax havens that explicitly provide the product of financial secrecy to whomever can pay the price.

The illegal outflow of money from African (and other developing) countries can occur through commercial, corrupt, and criminal means. In other words, illicit financial flows arise when:

- Multinational companies use absurdly complex subsidiary structures and various accounting maneuvers to siphon money out of the country of operation into shell subsidiary company in tax havens with minimal or no taxation so as to zero out their tax base owed in the original country. See this case study example by Action Aid highlighting the tax dodging strategies that multinational giant SabMiller uses to avoid taxation in Ghana.

- Corrupt government officials, politically exposed persons (PEPs) and other high ranking individuals cloak their finances in nameless offshore accounts, holding companies and trusts so as to completely disconnect their name as ultimate financial beneficiary to undertake corrupt activities such as receiving and paying bribes. See this article in The Guardian detailing the use of offshore accounts in the international FIFA corruption scandal.

- Criminals, terrorists and international cartels use certain bank secrecy services and tax havens to launder hundreds of millions of “ill-gotten” dollars so that the dirty money is washed clean of any suspicion. See the “Swiss Leaks” series by the International Center for Investigative Journalism highlighting these stories.

There are a number of estimates as to the magnitude of the problem in Africa. Some estimates provide a ratio of IFFs to development assistance that is 2:1, even 3:1. Another well known estimation posits that for every 1$ received in development assistance, $10 is lost through illegal flight from developing countries.

To put it in perspective, the illicit financial flows that have left Africa over the past fifty years are more than the entire continent’s outstanding debt bill. Thus, without this illicit outflow of money, Africa’s debt bill could have been cleared. To put it simply, the continent is hemorrhaging money.

Awareness of the problem of IFFs makes it very interesting and simultaneously disturbing to listen to the continuous circular conversations about aid and the never answered question of “Why isn’t aid working?” It is perplexing to hear these questions asked time and time again with little to no mention of the corrosive effects that illicit financial flows and aggressive tax avoidance practices have on domestic revenues in developing countries.

This seems to be a glaring error in the conversation. One huge reason development isn’t working is because at least as much money is being siphoned from the continent as is injected into it every year through aid money. To make matters worse, the money intended for development even goes through tax havens. According to a 2014 by Eurodad development finance institutions providing support for private sector development projects such as road construction often make their investments for development projects through tax havens. Thus, the absence of the topics of IFFs and tax havens from the development and aid effectiveness debates may not be so unintentional after all.

Maybe, if more efforts focused on the issue of IFFs rather than international development assistance, countries could crack down on illicit outflows, enabling them to increase their domestic revenue mobilization and become less aid dependent. As investment and development funds flow to African countries, the new Stop the Bleeding campaign is trying to redirect the conversation toward what is flowing out. Because, according to the campaigners, real change for African economies will not occur until the issue is addressed.

For those who like images, here is an infographic from Stop the Bleeding.